Spina, a city of water and wood

Spina was the most important port and Athens's main partner in the northern Adriatic. Founded around 530 BC along an ancient branch of the Po, it prospered for three centuries.Today the archaeological site is about 12 km from the sea, but in ancient times it was located at the mouth of the Delta, at the confluence of one of the Po's main branches and a dense network of secondary Apennine waterways.

The settlement was discovered in the early 1960s, during land reclamation works of the Valli di Comacchio. Despite decades of archaeological excavations, we know only about a small part of the site.

The settlement was founded on several emerging islets, behind the sandy dunes housing the rich necropolis.

Recent surveys have revealed a rational urban standard, with orthogonal axes with north-south orientation. The main arteries consist of wide water channels, bordered by long rows of posts, and perhaps covered by bridges and walkways. This regular grid of canals generated a Greek-style layout, with standard rectangular blocks, similar to the nearby Etruscan settlements of Marzabotto and Forcello (Mantua), or in the colonies of Magna Graecia.

An ancient seaport

Goods came to Spina from all over the Mediterranean. Wine, oil, and precious items from Greece, ointments and perfumes from the Near East, amber from the Baltic, and building and everyday materials from neighbouring areas.The commercial activity is demonstrated by the number and variety of imported products, with absolute precedence belonging to wine, transported in amphorae and consumed in the most precious of glassware.

Goods came to Spina from all over the Mediterranean. Wine, oil, and precious items from Greece, ointments and perfumes from the Near East, amber from the Baltic, and building and everyday materials from neighbouring areas.The commercial activity is demonstrated by the number and variety of imported products, with absolute precedence belonging to wine, transported in amphorae and consumed in the most precious of glassware.

For nearly two centuries, Athens supplies Padanian Etruria and the Alpine regions with wine as well as figured and black-glazed pottery. Fine exotic products as wine, oil, unguents, perfumes, and spices came from the Aegean, eastern Greece, and Egypt, as evidenced by specific vases and amphorae, not to mention the glass and alabaster unguentaria.

Amber was traded from the Baltic regions for centuries and continues to adorn the local female costume.

Greek and Oriental marble was also imported, while volcanic rock were used to make millstones. Even the most common stones, from the Apennines and the Alpine regions, was used for buildings, making weights, tools, and as gravestones.

From the mid-4th BC, the commercial routes move to the Italian peninsula, increasing exchange with Magna Graecia and Etruria.

Trading

Coinage was never adopted in Spina. Transactions took place through barter, weight units and bronze lumps.Trading in Spina took place without any coinage, but with a complex system of weighing. Bronze lumps (aes rude) were also used for transactions, as well as rectangular portions of thin ingots. Their proto-currency use is suggested by their standard weight values, as found in other contemporary trading cities in Northern Italy.

Many stone weights display numeral inscriptions, seen as weight units. The Etruscans knew several weighting standards, such as a light libra of 287 grams, and a heavy one of 358 grams. The latter is widespread in Spina, in Padanian and inland Etruria.

Thus, different systems for weights and for regulating trade coexisted in Spina, a further evidence of its commercial and cultural openness.

Products and workshops

Spina offered an abundance of trade goods, including cereals, meat, and salt, and products of workshops.

Exports consisted mainly of raw materials, including cereals and, in particular, the wheat cultivated in the entire rear region. The plain and nearby forests also provided timber, skins, livestock husbandry, especially pigs.

Salt manufacture was another traditional activity along the Adriatic coast, extracted from seawater through elaborate procedures. Salt was fundamental in farming and in the dairy industry, for food preservation and in tanning clothes.

The most documented handicraft is pottery production. Several potter's workshops were active in Spina, located primarily in outlying areas, able to supply the local market with thousands of vessels. Manufacturing traces are production waste, kiln tools, as well as figured stamps, graffiti and letters used as trademarks.

Woodwork and marsh grasses processing was widespread in a coastal settlement like Spina.

Exchange at the table

A typical mixture of port cultures is also reflected at the table. Archaeological findings tell us of a varied cuisine, open to exotic eating habits. In the port of Spina, different culinary practices met and melted every day. Beginning in the 5th century BC, a new set of cooking ware was imported from the Greek world.

Also new recipes and a true gastronomic culture arrived together with the new pots.

Scientific analyses prove that many varieties of vegetables, legumes, and fruits were eaten in Spina. These were both cultivated and harvested in the nearby forests, in addition to being imported. Olive oil and wine, as well as vinegar, honey, and spices were also essential on a Spinetic table.

In the kitchens, soups and stews with vegetables, legumes, and meat were prepared, accompanied by loaves and flat bread. The meats of both domestic and wild animals as well as slices of seasoned fish with elaborate sauces were roasted.

Spina households

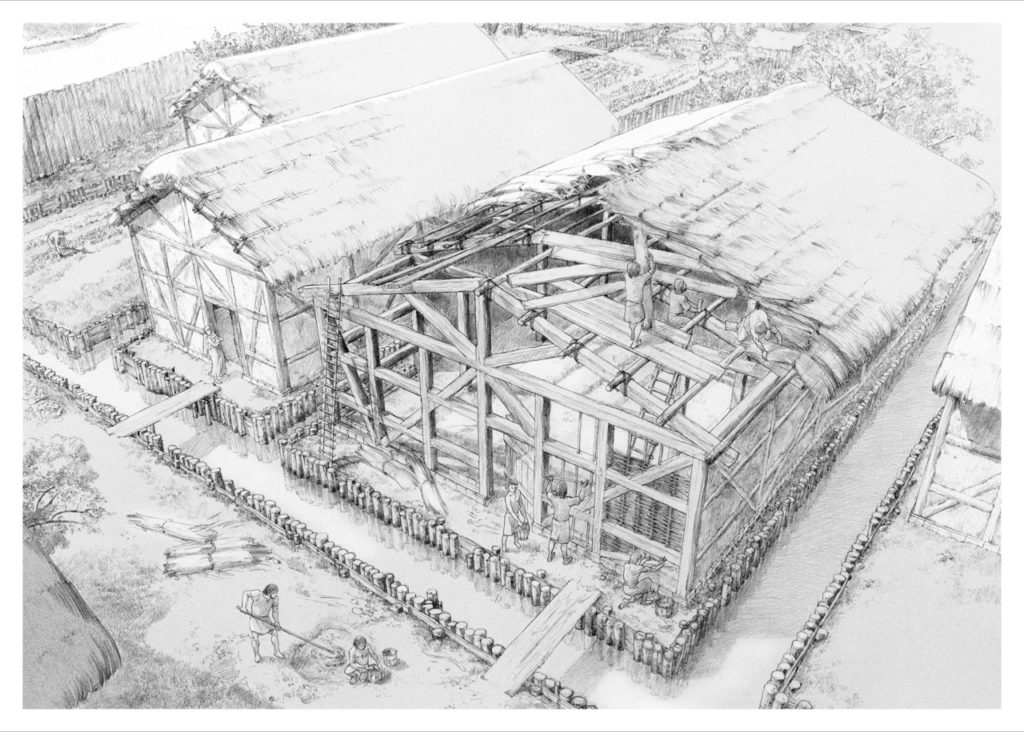

The buildings in Spina were made of lightweight materials, especially timber, clay, and marsh grasses, according to the lagoon environment and the exploitation of natural resources. Architectural solutions were highly specialized. While the more antique houses were similar to log house constructions having horizontal logs interlocked at the corners by notching, the most recent houses instead display a technique with long rows supporting clay walls.

Roofs were constructed using plant materials, with a limited use of roof tiles. A particular painted plaster was common for insulating the walls of the buildings from humidity.A domestic context. Excavations take a picture from 2,500 years ago.

Recent excavations have documented the history of a house between the late 5th and the mid-3rd century BC. The building was bounded on three sides by canals, reinforced with vertical posts, and equipped with wooden walkways. Around 400 BC, the walls of the house were constructed using horizontal wooden beams and then plastered. In smaller rooms daily activities took place, including spinning, weaving, and food preparation. A minor canal separates a space protected by a roof for handcrafts.

Inside the main room, at the bottom of a hole next to a hearth, four valuable gold plates, depicting three soldiers and a female figure, were buried. They could be a part of small wooden box, hidden in a safe place.

The end of Spina

The myth of a lost city.Spina disappears during the 3rd BC, after only three centuries of existence. The multiple causes have not been fully clarified yet. During the 4th BC the political and commercial arrangements change across northern Italy, with the invasion of the Gauls, the expansion of Syracuse, and the decline of Greek influence.

Even the environment was changing, as testified by ancient literary sources which wrote about the progressive displacement of the coastline during the Imperial age, was already 15 kilometres to the east in respect to the Etruscan period.

It is also possible that a military attack by the Celts took place. In fact, the upper layers have yielded traces of fires and several clay sling bullets, incendiary projectiles thrown by the besiegers.

After the end of the city, only scattered settlements survived during the Roman times. The ancient splendour was now only a memory, hidden by mud and water. The myth of a lost city was born.